Anti-‘Critical Race Theory’ Laws Are Bad Enough. Don’t Exaggerate Their Impact.

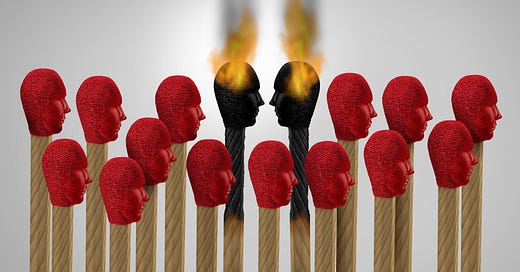

Magnifying the issue only further inflames partisan rancor and makes it harder for teachers to teach and students to learn.

It’s bad enough that states are passing laws banning the teaching of “critical race theory” and other concepts in public schools. Let’s not make things worse by exaggerating what’s going on.

It’s been widely reported that the school district in Southlake, Texas, is requiring teachers to include “both sides” of the Holocaust, apparently because that’s what state law demands. The reports stem from a school district administrator’s advice to teachers last week about new legislation. The law requires, she said, that if they have a book about the Holocaust in their classroom libraries, “make sure … you have one that … has other perspectives.”

It turns out this was a wildly mistaken interpretation by a well-meaning official who was—like the teachers she was addressing—clearly exasperated by legislative efforts to control what goes on in the classroom. “You are in the middle of a political mess,” the administrator observed. And it’s a mess not confined to Texas. At least eight states have passed laws attempting to restrict teaching about race and other controversial subjects, and another 20 have legislation in the pipeline.

What the Texas law actually says, though, is that teachers can’t be “compelled … to discuss current events or widely debated and currently controversial issues of public policy or social affairs.” If teachers choose to discuss such events or issues, they “shall, to the best of their ability, strive to explore such issues from diverse and contending perspectives without giving deference to any one perspective.”

Any reasonable reading would exclude the Holocaust from this requirement; it’s obviously not a “current event,” nor is it “widely debated and currently controversial.” Plus, the discussion in Southlake was about books in classroom libraries, and the law doesn’t apply to those. The legislator who wrote the bill denied that it required teachers to get rid of books presenting only one perspective on the Holocaust, and the district superintendent stated that the district understands that “this bill does not require an opposing viewpoint on historical facts.”

No doubt recent tensions in Southlake have something to do with the administrator’s mistake. Some Black students and their families, complaining of racist taunting by white students, have called for mandatory cultural sensitivity training for teachers and students. That has sparked vigorous pushback from a vocal group of conservative parents, and teachers have had to contend with confusing guidelines from the district about what books are allowed in classroom libraries. It’s possible some Southlake parents have demanded that “both sides” of the Holocaust be covered, but the only evidence is the administrator’s remark that the issue has “come up.” If true, that’s shocking, but it’s far from an official state requirement that it be done.

Some news reports have included at least some of this context, but one account that did not came from historian Heather Cox Richardson, who writes a widely read newsletter. After describing the Southlake administrator’s remarks as though they were a valid interpretation of the Texas law, she went on to express dismay about “another [Texas] law” that specifies “what, exactly, social studies courses should teach to students.” (In fact, it’s the same law—just the Senate version of the House bill the administrator was referring to.)

Cox Richardson gave examples of some texts and topics the bill required—including the Declaration of Independence, and the 13th, 14th, and 19th Amendments—and some that had been stricken out: the writings of Frederick Douglass, the history of white supremacy, the 15th Amendment (which gave Black men the right to vote). This sort of historical “editing,” Cox Richardson wrote, “warps what it means to be an American.”

To be sure, the listing was highly partisan: Republicans in the state Senate struck out texts and topics that Democrats had inserted when the bill was in the House of Representatives. But Cox Richardson, who characterized the law as delineating social studies “standards,” seemed to assume that it would bar schools from teaching about the omitted items. That’s not the way standards work. More fundamentally, it’s not the legislature’s job to create academic standards; that’s the province of the state board of education.

In fact, the final version of the bill, signed into law by Governor Greg Abbott in September, removes the list of texts entirely, merely directing the board of education to ensure that students develop an understanding of concepts like “the fundamental moral, political, entrepreneurial, and intellectual foundations of the American experiment in self-government,” using “the founding documents of the United States.”

The Texas legislation is still ill-advised and dangerous. For example, it prohibits teaching certain concepts that are defined vaguely, such as the idea that “an individual, by virtue of his or her race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously.” But, just as the law was never intended to require that “both sides” of the Holocaust be presented, the listing and de-listing exercise that Cox Richardson denounced was already a moot point when she wrote her critique.

The problem is not just that these accounts were inaccurate. Reporting or commentary that makes political battles over curriculum appear even worse than they are will likely fan the flames of an alarming conflagration. Parents protesting the teaching of what is often vaguely called “critical race theory” are already commanding attention that is probably disproportionate to their numbers—sometimes with the help of prominent conservatives. If they’re made to look more successful than they’ve actually been, it could only embolden them further. It’s also likely to intensify reaction on the left, ratchet up the current cycle of demonization on both sides, and continue to magnify what appears to be essentially a non-issue.

There are, to be sure, disturbing accounts of students being subjected to what even some politically progressive parents see as indoctrination, or being required locate their identities on a matrix of oppression. But the vast majority of teachers aren’t teaching anything they consider “critical race theory.” One survey found that more than 96% of respondents said their schools didn’t require them to teach it, and only 45% favored giving teachers the option. Another survey found that only 8% of K-12 teachers had ever taught or discussed the topic.

I suspect the majority of parents and teachers would agree that students should learn generally accepted facts about current events and history, including its more difficult chapters, with exposure to multiple perspectives when appropriate. But trying to legislate which facts should be taught, and when multiple perspectives are appropriate, is an exercise fraught with danger, and one that threatens to make teachers’ already difficult jobs virtually impossible.

It also threatens to prevent students from acquiring a meaningful education. If teachers are afraid to discuss history and current events—one Southlake teacher described herself as “terrified”—many children won’t learn things they need to understand to be academically successful and carry out their responsibilities as citizens of a democratic society.

In Tennessee, for example, one conservative parent group has launched a baseless attack on an elementary literacy curriculum that does a far better job of building academic knowledge and vocabulary than the standard approach—which avoids content in favor of comprehension “skills,” like “finding the main idea,” that are largely illusory. If such groups succeed in getting high-quality curricula banned from classrooms, all students will suffer, and especially those from less educated families who are less likely to acquire academic knowledge outside school.

Difficult as it may be to find common ground in the current polarized environment, that’s what will be necessary if we want our children to thrive. If parents don’t feel a curriculum covers everything it should, or mischaracterizes certain events, they’re free to supplement it with their own perspectives or materials outside school doors, as parents have done for generations—and some are doing now. Rather than stoking further division, however unintentionally, the media and commentators might try focusing more attention on developments like that.

This post originally appeared on Forbes.com.