New Reports Suggest Schools Can Boost Social Mobility

Class is more significant than race to academic achievement--and a big factor is the kind of knowledge schools could provide.

Because of the way test scores are reported, we tend to see gaps in academic achievement in terms of race and ethnicity—and, as a result, proposed solutions often focus on measures like diversifying the curriculum and combating racism. But, as I’ve previously argued, if we view the data through a different lens, it becomes clear that factors other than race are at least as important.

A new report from the Thomas B. Fordham Institute now provides additional support for that argument, concluding that socioeconomic factors like parental level of education explain a substantial amount of racial and ethnic disparities in achievement.

Education researchers Paul Morgan and Eric Hengyu Hu, both at SUNY Albany, analyzed data collected by the federal government that follows children through their elementary school years. They relied on a set of variables they call “SES+.”

SES stands for socioeconomic status, which is usually determined by family income and parental education and occupation. The “plus” part consists of factors like with whom a child lives, how much parents read to a child, their level of “warmth,” and if a family has rules around TV-watching.

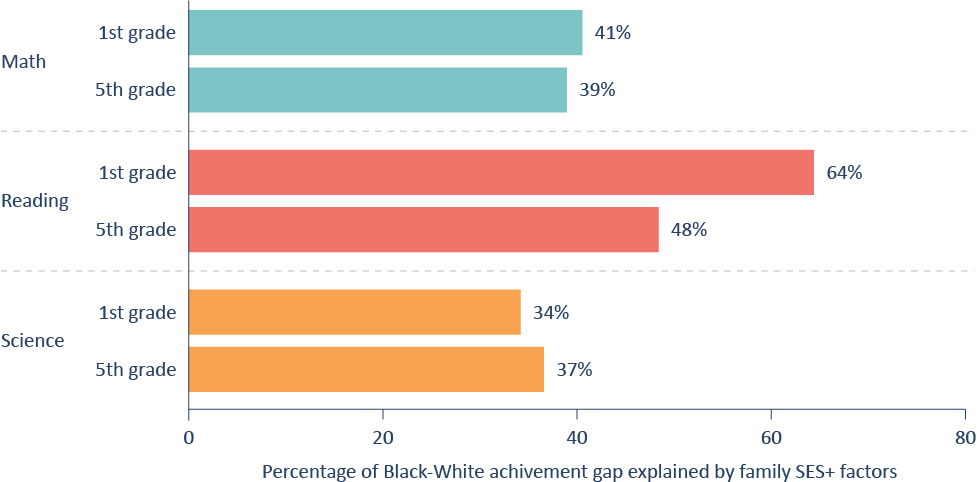

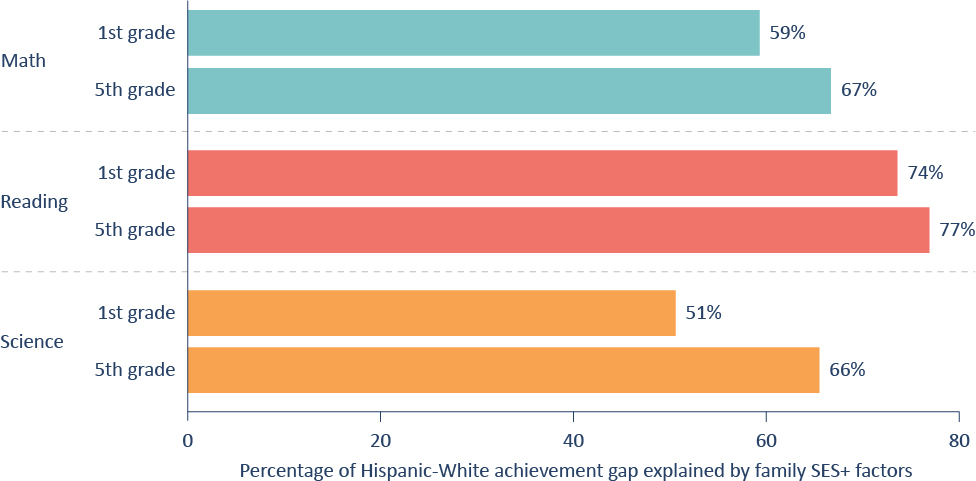

Taken together, these factors explain between 34 and 64 percent of the gap between Black and white students—across reading, math, and science—and 51 to 77 percent of the gap between Hispanic and white students. (The percentage varies by subject and grade level.)

Figure F-1. Family SES+ explains more of the Black-White achievement gap in first grade reading than in other subjects and grade levels.

Figure F-2. Family SES+ explains more of the Hispanic-White achievement gap than the Black-White achievement gap.

(Graphs from Morgan and Hu, Explaining Achievement Gaps: The Role of Socioeconomic Factors, Thomas B. Fordham Institute)

The SES+ factors were most explanatory for the gap in reading scores, probably—as Fordham president Michael Petrilli speculates in an introduction—because parents play a larger role in transmitting the kinds of language abilities that support reading ability. And yet, “plus” factors like the amount of time parents spent reading to their children were found to be relatively insignificant.

What was significant across subjects were two of the standard SES factors: household income and parental level of education. Income was more significant for the Black-white gap and parental level of education was more significant for the Hispanic-white gap, but in both cases these two factors were at the top of the list.

SES+ doesn’t fully explain these gaps, especially the Black-white one. But the Fordham researchers conclude that those factors are significant enough that it would make sense to emphasize race-neutral policies in addressing them.

The report contains a number of thought-provoking subsidiary findings, but the bottom line—at least for my purposes—is that SES, and particularly level of parental education, explains a lot of the gap in test scores between racial and ethnic groups.

Another Study: Race Has Declined in Significance for Social Mobility

That finding dovetails with another study, by economist Raj Chetty and colleagues, finding that class has become increasingly important to social mobility when compared to race. That study is based on another set of data collected by the federal government on 57 million children in two cohorts, one born in 1978 and the other in 1992.

Again, there’s a lot of nuance in the study, but I’ll focus on the finding that when the two cohorts are compared, Black kids experienced more of an increase in social mobility than white kids did.

That means that a white kid born into poverty in 1978 was more likely to make it out of poverty than a white kid born in 1992. For Black kids born into poverty, the situation was the opposite: the 1992 cohort was more likely than the 1978 cohort to move out of poverty. As the researchers put it, there was “a remarkable 72% reduction in the racial gap in the intergenerational persistence of poverty over just 15 years.”

This doesn’t mean race has become insignificant. White kids are still more likely to experience upward mobility than Black kids, at all income levels. But compared to the previous cohort, poverty has become less persistent for Black kids than for white kids.

Chetty and his co-authors don’t explicitly link this phenomenon to parental level of education, but that’s a significant factor in “class” or SES. “I’ve thought for a while,” Matt Yglesias observed in a post about the study, “that Kamala Harris would be an ideal person to talk frankly about how, yes, she has faced unique and difficult challenges as a Black woman, and also she’s the daughter of two professors and had advantages in life that many people of all races lack.”

Indeed she did—as the Fordham study underscores. She may not have grown up wealthy, or even in an intact two-parent family, but she had the benefit of the fairy dust sprinkled by highly educated parents.

Of course it’s not actually fairy dust. A lot of it is the academic language and vocabulary that such parents transmit to their children in informal ways—not just by reading aloud. The transmission process is largely unconscious, consisting of routine casual exposure to the kind of knowledge generally assumed by the school curriculum, including lots of back-and-forth conversations about the wider world.

What Schools Can Do to Spread the “Fairy Dust”

The good news is that parents aren’t the only ones who can sprinkle that precious dust; teachers can do it too. For that to happen, schools need a coherent, content-rich curriculum beginning in the early grades. Once that’s in place, they need to implement teaching techniques backed by cognitive science that enable all students to understand, analyze, and retain that content.

One powerful way to do that is to teach kids explicitly how to write, beginning at the sentence level, and to embed writing activities in content across the curriculum. That’s also an excellent way to familiarize students with the peculiar vocabulary and syntax of written language, which is often a barrier to comprehension.

Unfortunately, only a minority of schools are currently doing these things, making reading, writing, and learning in general much harder than they need to be. The result is that the students who thrive in our education system are those who would probably thrive in any system: the kids who are highly motivated and well-organized, or who have parents with the resources to provide the support they need. The others are usually left to flounder.

And yet, a few manage to thrive. What can their experience tell us about the impact of academic achievement on life chances? Does it really make a difference to your social mobility if you do well in school?

A Third Study: Academic Achievement and Social Mobility

Yet another report—this one from TNTP—sheds some light on that question. It’s based on yet another set of federal data that followed children born between 1980 and 1984 into adulthood. The report confirms that few children who live in poverty as adolescents are able to move up the ranks of society. Only 30 percent are earning a living wage by age 30, for example, as opposed to 60 percent of those from more affluent families.

But academic achievement makes a powerful difference. Poor kids with strong academic outcomes are three times as likely to earn a living wage and twice as likely to report high levels of well-being by age 30 as compared to their peers with weak academic outcomes. And academic prowess predicts social mobility regardless of whether a student goes to college. While the federal database recorded other high school factors, such as social networks, “only academic outcomes predicted both economic and social mobility.”

Let’s put this all together:

Academic achievement has more to do with level of parental education than race.

A likely reason: highly educated parents transmit academic knowledge and vocabulary to their children.

Schools can do a better job building that kind of knowledge for all students, and especially those who aren’t able to get it at home.

Children from poor families who achieve academically are far more likely than others to experience upward social mobility as adults.

Therefore, if schools do a better job of building knowledge for kids from less highly educated families, they can significantly improve their chances of upward mobility—and probably their children’s.

Note that these are my own conclusions, not those of the authors of any of these reports. They focus on other kinds of solutions.

The authors of the Fordham report recommend policies like helping parents further their education, expanding early childhood education, and providing poor families with economic support.

Chetty and his colleagues suggest initiatives like job training and increasing cross-class interaction in schools and neighborhoods. (They found that growing up in a community with a high level of employment made a dramatic difference—and that children’s outcomes were especially influenced by the employment rates of parents whose kids they were most likely to come into contact with.)

The TNTP report concludes that students experiencing poverty should have more access to “good teaching and grade-level content,” but they emphasize that strong academic outcomes don’t completely outweigh the effects of poverty. Even poor kids who do well academically earn no more at age 30 than an average student from an affluent family. What’s needed, they say, are opportunities for poor kids to build social capital, become engaged in their communities, and be guided into careers.

All these suggestions have merit. But they overlook something that—while it surely won’t eliminate racial and socioeconomic equities—can have a pretty dramatic impact: changing how and what schools teach so that all students have a chance to succeed academically and in life.

Schools can’t boost the income of students’ families or increase levels of parental education. But teaching kids stuff they need to know, in a way that works, is their core mission, and it could help bring about a more equitable society.

Compared to other proposals for addressing inequity, it’s also a fairly doable task. At the same time, we have a long way to go before most schools in this country are even aware of the need to undertake it. Why not focus attention on that as one powerful way to narrow academic gaps and increase social mobility?

Couldn't it be that poor kids who do better in school tend to be smarter, more conscientious, etc? I know Eric Hanushek has done work purporting to show that better instruction actually results in better outcomes for students, but this study, at least as described, does not seem to show this.

I am skeptical that "racism" has much effect on learning outcomes in this day and age. Family, community and quality of the learning environment (school) are probably by far the greatest factors. Throw in the expectations of one's subculture about the value of academic achievement. If your subculture doesn't respect academic achievement you are primed to fail.

The most important factor (as this piece notes) is family, educated parents and an intact marriage predict success.