How to Help Older Students Who Struggle to Read

Many students above third grade need help deciphering words with multiple syllables

Many students above third or fourth grade struggle with reading. Evidence suggests a large contributing factor has been overlooked—and there may be a fairly simple way to address it.

A lot of attention has been paid to problems with early reading instruction, most of it focused on the need to teach phonics systematically. As of April 29, 38 states and the District of Columbia had adopted policies or legislation designed to ensure that happens.

In addition, educators in many school districts have recognized that academic knowledge and vocabulary play a key role in reading comprehension. They have retooled their elementary curricula and instruction to include building that knowledge.

These efforts are hugely important. But what if many students will nevertheless continue to struggle with reading in middle and high school, when texts become more complex? That’s clearly the case now, with 30% of eighth-graders reading below a basic level.

One question that hasn’t gotten enough attention is whether students are able to make the transition from deciphering, or “decoding,” simple words to decoding the words with multiple syllables they encounter at higher grade levels.

“If kids have learned to read the word cat,” says literacy expert Rebecca Kockler, “they’ll try to read education but pronounce the ‘cat’ in the word as cat. They all know the word education, so it’s not a vocabulary issue.”

Reading Reimagined

Kockler made her name, at least among education policy geeks, as a key official in the Louisiana Department of Education under former Superintendent John White. Alongside White, Kockler helped shift the state to significantly better foundational reading skills instruction and the widespread adoption of knowledge-building elementary curricula.

But Kockler says that while she and her colleagues saw “growth in every metric” in the elementary grades, “we would often see a peak in fourth grade and then a decline. I couldn’t understand that.”

To figure it out, she embarked on her current project, Reading Reimagined, a research-and-development initiative aimed at improving reading outcomes for students above second grade, especially those from historically disadvantaged and low-income communities. The project aims not only to fund research in that area but also to bridge the gap between research and practice, coming up with evidence-based solutions.

The four-to-five-year, $40-million project is being carried out under the aegis of AERDF (Advanced Education Research and Development Fund) and is now about halfway through its lifespan. AERDF is simultaneously shepherding two other research initiatives and is about to launch a fourth. Its key funders are the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, and the Walton Family Foundation.

Kockler hypothesizes that the reading struggles of many older students are due in large part to two issues. One has to do with “linguistic difference.” If a child’s family and community speak a variant of English that differs from the kind generally used in books and by teachers—for example, African-American English—it could be harder for them to decode words and connect those words to their meanings.

The Decoding Threshold

The other issue has to do with difficulties in decoding multisyllabic words. Kockler points to a couple of large-scale research studies that have identified a “decoding threshold.”

In theory, students’ reading comprehension ability should improve as they advance to higher grade levels—and it often does. But the researchers found that if students are above fourth grade—past the point where they’re likely to get decoding instruction—and their decoding ability is below a certain level, they’re “extremely unlikely [to] make significant progress in reading comprehension in the following years.” The studies, which were conducted in a high-poverty, largely African-American district, found that almost 40% of fifth-graders and 20% of tenth-graders included in the sample fell below the decoding threshold.

When older students experience decoding difficulties, there is often no meaningful help available. Teachers above the early elementary grades generally aren’t trained in decoding instruction, and reading assessments usually don’t focus specifically on decoding ability. The problem is typically assumed to be comprehension, and students are given more instruction and practice in comprehension skills like “finding the main idea.” But other studies have also suggested that decoding may be a significant factor.

The link between decoding ability and comprehension has to do with limits on the mind’s ability to take in new information. If students are expending too much cognitive effort on decoding words, they don’t have enough capacity left for comprehending the text. In cognitive science terms, they’re experiencing too much “cognitive load.” Decoding needs to become more or less automatic for students to be able to focus on meaning.

The solution is to provide students with decoding instruction at higher grade levels—but not, Kockler says, the same kind that the evidence indicates works in K-2. At those lower grade levels, children need to practice the phonics patterns they’ve learned using simple “decodable” texts (think, “The cat sat on the mat”). For older students, Kockler says, “you have to do this simultaneously with building knowledge” and other kinds of instruction—for example, morphology (understanding prefixes and suffixes). And, she says, “you have to do it in the context of meaningful text.”

Readable English

Another new initiative I’ve recently become aware of seems to align with that description. Called Readable English, it was developed by a former reading specialist, Ann Fitts. Fitts was struck by the “sheer amount of memorization” necessary to learn to decode English, a language in which many letters are capable of producing more than one sound.

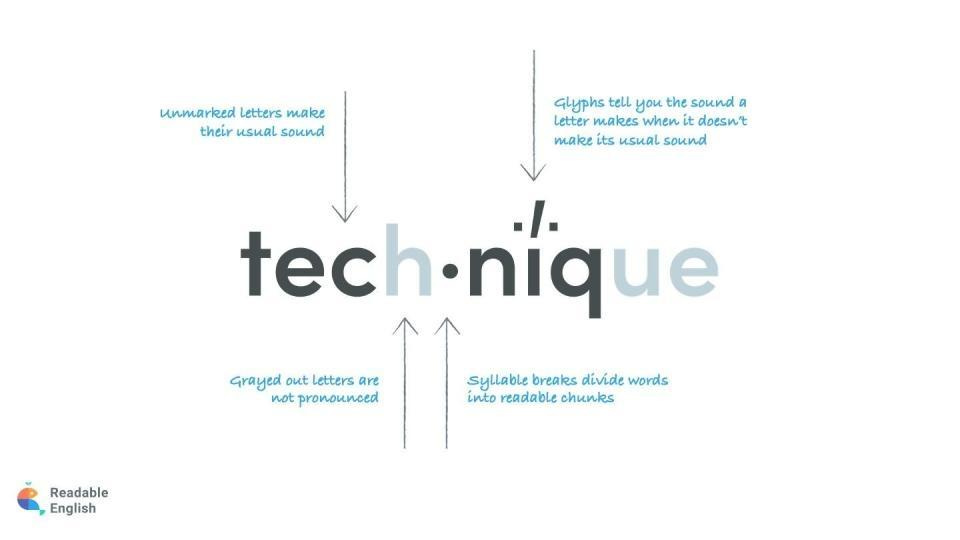

A key part of the approach is to use technology to mark up text in a way that makes complex words easier to read. A dot appears between syllables, silent letters are greyed out, and diacritical marks—or “glyphs”—are inserted over certain letters to indicate they’re making a particular sound.

The word technique, for example, would be marked up like this:

In the first phase of the intervention, students learn phonics patterns, but they also learn 21 glyphs that represent non-standard letter sounds. The next phase has students practice reading marked-up text and converting text from standard English to the Readable English version, using either texts of their own choice or those assigned by a teacher.

Students are able to turn the mark-up function on or off for individual words. The intervention also includes comprehension, writing, and vocabulary-building activities. Eventually, students should be able to use the Readable English tool as needed to read grade-level texts that are part of the core curriculum.

Research Studies

At least three peer-reviewed studies of Readable English have been published—one with older elementary students, one with middle school students, and one with high school students. The studies were done in high-poverty rural schools and conducted during the pandemic. All found statistically significant and meaningful positive results on various measures, including reading comprehension.

In the middle school study, students who got Readable English grew an average of two grade levels in reading comprehension in less than six months—a result researchers called “surprising”—while the control group experienced a one-month loss. In the elementary study, the Readable English students gained about nine months in reading comprehension after 45 to 60 hours of instruction; the control group gained three months.

The assessments used regular English text rather than a marked-up version, indicating that students were able to successfully transition from one mode to the other. In one of the studies, researchers compared using the Readable English mark-up to learning to ride a bike using training wheels. At a certain point, the “wheels” can come off, and students can transfer their word-reading knowledge to regular text.

In both the elementary and middle school studies, the control group was getting a knowledge-building curriculum that also teaches foundational skills systematically at lower grade levels (Amplify CKLA and Amplify ELA). Teachers in the study were trained in the Amplify curricula and had been using it for at least three years. That suggests that even if students get a high-quality literacy curriculum, many may need additional help to become proficient readers of complex text.

The researchers found that Readable English was cost-effective and easy for teachers to implement. Unlike most reading interventions, it doesn’t require that students miss regular class time, and it enables them to read grade-level text relatively quickly.

A Rare Success At The High School Level

Perhaps the most impressive of the studies is the one involving high school students. Although the sample was small—just 25 students, including both the treatment and control groups—the results were dramatic, especially considering that few interventions work at the high school level.

The students in the study were in alternative high schools, which are likely to enroll the most disaffected and discouraged teenagers. All had been identified as having a reading disability, and they were over four grade levels behind where they should have been, on average.

The schools used a “credit recovery” platform as the curriculum. Credit recovery, the researchers wrote, has become the “de facto education solution for students in alternative school settings in which one teacher is supposed to support instruction for four grade levels and all core courses.” The program used by schools in the study was “text-heavy” and challenging, including authors such as Shakespeare. Often, the researchers observed, students in alternative schools are simply “warehoused until they can drop out.”

The control group got tutoring in phonics and “sight words,” which don’t conform to typical phonics patterns, while the students who got the Readable English intervention used its software to mark up the credit recovery text. The latter group experienced meaningful improvements in various aspects of reading, including growing more than one grade level in reading comprehension—which, the researchers wrote, “is remarkable considering three months of learning loss [were] sustained by the control group.”

An important feature of Readable English, the researchers observed, is that it allowed students to choose passages that corresponded to their interests. It was apparent, they said, that despite their struggles these students had “a wealth of vocabulary knowledge learned both from core courses (e.g., earth science, math, history, etc.) and from individual interests.” Anecdotally, their behavior also improved considerably, with one student who had been given to regular physical and verbal outbursts “transformed into a calmer, happier person.”

In addition, 13 of the 14 students in the Readable English group passed their end-of-year state tests in December, and the remaining student was able to pass the test in May. In the control group, only one of 11 students was expected to pass in May.

Potential To Transform Reading Instruction

Australian cognitive psychologist John Sweller, the father of cognitive load theory, has endorsed Readable English as an effective way of modulating the burden that decoding imposes on students’ working memory. “Based on theory and data,” he has written, “I can recommend Readable English in the strongest possible terms. It has the potential to transform the teaching of English.”

The difficulties posed by English spelling have been a source of complaint for centuries. Would-be reformers have noted that the word fish could be spelled ghoti, using the pronunciation of gh in tough, o as in women, and ti as in nation.

Of course, English is actually more predictable than that; if you find gh at the beginning of an English word, for example, it won’t be pronounced as f. Still, it’s clear that students in English-speaking countries face greater challenges than students in, say, Spanish-speaking countries, where the spelling system is more phonetic.

Given that it’s unlikely English spelling will be rationalized anytime soon, a method like Readable English holds promise for the many older students who struggle to read multisyllabic words. We do need more research on it, especially with more diverse student populations, and it’s surely not the only thing students need to be academically successful. But it could be a necessary and even transformative intervention for a group of students who have been left to experience failure for too long, damaging their self-concept and life prospects.

This post originally appeared on Forbes.com. It has been updated to correct an assertion that no English words begin with “gh.”

SO, we are again spending tens of millions to again reach the conclusion that alphabetic languages were obviously designed to be decoded, and that students do best when we teach them to decode. How insane.

Everything discussed here was fully revealed in 1977 by the largest instructional research project ever conducted ("Project Follow Through"), which demonstrated that explicit, "direct" phonics curricula overwhelmingly outperform all other styles of reading instruction, and that in fact a particular curriculum called "Direct Instruction" outperformed all other major curricula of that era. Not only did Direct Instruction teach phonics explicitly, but it massively incorporated the "Readable English" concept that is presented here as if it were something new.

Yet Direct Instruction curricula are virtually unknown in the public schools; I challenge you to find a public school district anywhere in your area that uses it. But strangely the "home" versions of it are immensely popular with home schoolers, consistently rating at or near the top of Amazon's "Parenting & Family Reference", "Language Experience Approach to Teaching" and "Family Activity" categories. How could this be? How could so many untrained home-schooling moms make such incredibly wise decisions when the public schools, decade after decade, cannot?

The answer is that public school administrators have a revolving door with curriculum publishers, and curriculum publishers don't make money selling proven curricula that schools would never replace until the pages wear thin. Curriculum publishers make money churning the schools through one ridiculous fad after another, which is why they're also in bed with quack university professors who are always coming up with yet more educational snake oil.

The never-ending saga of preposterous public-school reading instruction has been happening since well before 1955, when Rudolf Flesch published "Why Johnny Can't Read". We've known for decades, no centuries, that alphabetic languages were designed to be decoded. Non-indoctrinated home-schooling moms understand this perfectly; they don't need multi-million dollar research results to understand the obvious. The endless waste on researching what we already proved decades ago is absurd. Our real problem is the economic model of the public schools, which is immune to negative feedback from parents. So long as parents have no say over where their school tax dollars go, making the endless failure of the public schools immune from funding consequences, public school administrators will buy preposterous, faddish curricula from utterly corrupt publishers, with the expectation that they'll have cushy post-retirement jobs (with those publishers) selling more crap-o-la to their successors. READ AND WEEP: http://mychildwillread.org/the-problem.shtml

Great Article!! Very Informative