A Dispute About Sentences

It's clear many students don't understand the concept of a complete sentence, but we can fix that.

Despite the fact that I haven’t posted anything on this Substack in weeks, the number of my subscribers continues to rise. It now stands at almost 9,500. I’m grateful for that—and also feeling guilty that I haven’t offered up any fresh content lately. It’s occurred to me that if you’re a new subscriber, you may be wondering why you even bothered signing up for this newsletter!

I have a couple of excuses. First, I’ve been traveling a lot for speaking engagements (I’m writing this, or at least beginning to write it, in an airport, on my way from one engagement to another), and I expect that to continue for a while. Second, I’m supposed to be writing another book and need to find time to actually do that (I hope my editor isn’t reading this!).

So I’ve decided to try to write some more informal posts that won’t first go up on Forbes, which is my usual process (I’m allowed to republish Forbes posts after five days have elapsed).

Top of mind right now for me is a recent post by my friend Daisy Christodoulou—and if you’re not already a subscriber to her Substack, called No More Marking, I highly recommend it, along with her books. Daisy is based in England, and American readers might find some of her allusions to the education system there a bit mystifying, but she also often provides keen insights about writing, assessment, and learning in general that are universal—or at least relevant to the American context.

Daisy works for a company called No More Marking (hence the name of the Substack), NMM provides schools with a method of assessing writing, called comparative judgment, that is less labor intensive and more reliable than the usual approach.

Daisy’s recent post was about why it’s important for assessment to combine multiple-choice questions with samples of actual student writing. What caught my eye was what she had to say about sentences.

As readers of this Substack may know, I’m the co-author of a book called The Writing Revolution, which is a guide to a method of writing instruction that—in contrast to most other approaches—begins at the sentence level.

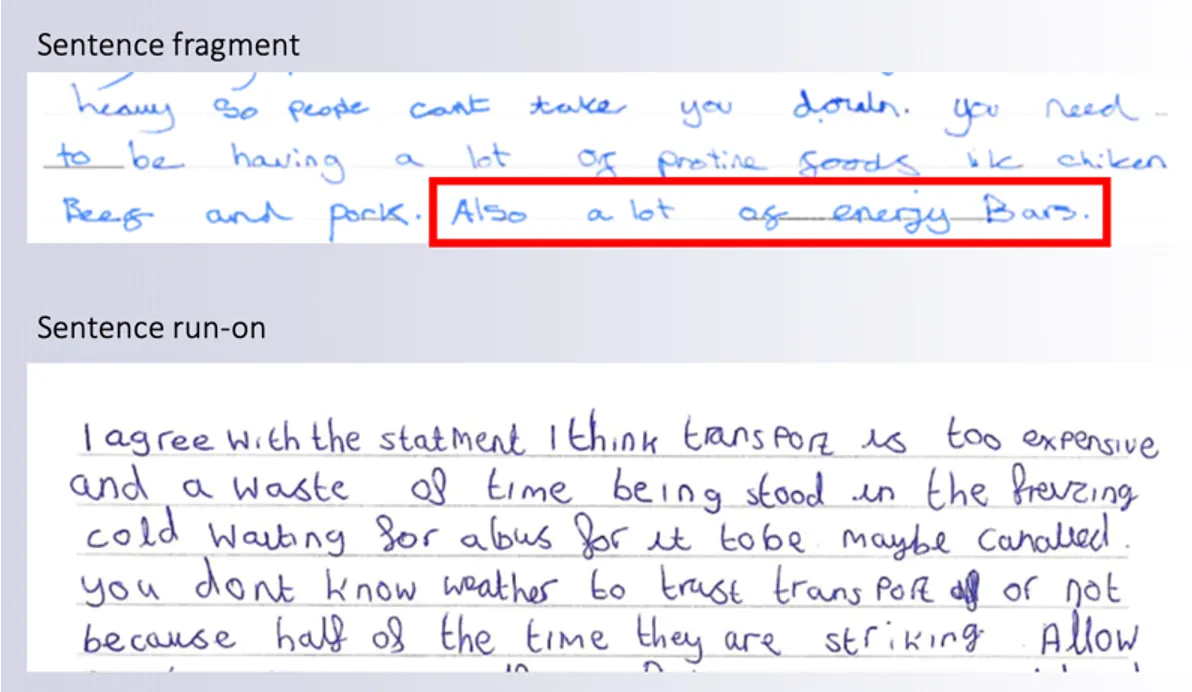

In her recent post, Daisy observed that after evaluating about two million pieces of student writing, NMM has noticed that “students often struggle to write accurate sentences. In particular, students will often write sentences that are incomplete (fragments) or that are too long (run-on sentences). These both make it harder to understand their meaning.”

To illustrate, Daisy included the following examples of student writing:

She also included two multiple-choice questions from a set of 20 that NMM had used to shed some light on why students were making these mistakes. The questions were given to about two thousand students in England in the equivalent of fourth grade.

Although the two questions are similar—both are designed to see if students can distinguish between complete sentences and fragments—the results were quite different. For the question on the left (#5), 91% got the right answer. For the question on the right, #6, only 13% did.

Why the difference? Daisy speculates that when you don’t really understand what makes a sentence a sentence, you go by surface features—in this case, length. The correct answer for question #6 consists of only two words, and that apparently doesn’t seem long enough.

This result didn’t surprise me. Years ago, when I was trying to tutor some high school students, I noticed that their writing was full of incomplete sentences. To try to figure out what the problem was, I showed them the following dependent clause: “Although I drank the glass of water.” All four of them thought it was a complete sentence. After all, it had a subject and a verb—not to mention “surface features” like a capital letter at the beginning and a period at the end.

Objections on Twitter

Although I’m kind of trying to avoid Twitter these days (yes, I still call it Twitter), I was so struck by this information in Daisy’s post that I tweeted out a link to it, along with a screenshot of the two questions and the statistics about correct answers.

A couple of people then took issue with the questions. One objected to the wording: “Only one of the following sentences is correct.” She argued that framing implied that all of the choices were sentences. Therefore, she said, students were likely to assume they were being asked which of the sentences was correct in terms of its content.

I could see that argument if the sentences—or “sentences”—were about something that was factual or objectively verifiable. But I think even fourth-graders would see the absurdity of being asked whether, for example, it’s more substantively correct to say “A great film” or “Enjoyed the film,” when they don’t even know what film is being referred to.

A second tweeter argued that some of the incomplete sentences actually were sentences—“minor sentences,” as she put it, but the kind of sentences you see “all over the place.” She gave as examples excerpts from The Road, by Cormac McCarthy (“Darkness implacable. The blind dogs of the sun in their running.”) and dialogue from Pride and Prejudice (“Is he married or single?” “Oh, single, my dear, to be sure! A single man of large fortune; four or five thousand a year.”) Maybe, she suggested, students thought some of the “minor sentences” in the multiple-choice questions were bits of dialogue, or possibly poetry.

At first, this seemed to me like a possibly more valid objection than the first one. Fourth-graders presumably haven’t read The Road or Pride and Prejudice, but they’ve surely seen incomplete sentences used as dialogue in books.

But as Daisy’s examples of student writing show—and as NMM has seen in millions of writing samples—students are routinely using incomplete sentences when they’re not trying to write dialogue or poetry. Yes, if you’re Cormac McCarthy, you can get away with using sentence fragments for effect—and even if you’re nine years old, you might legitimately do that if you’re engaging in creative writing. But in many situations, it’s important to write in complete sentences, and students who don’t understand what they are will be at a disadvantage.

What’s really tricksy here?

Both of the individuals who raised objections on Twitter seemed to be arguing that the multiple-choice questions were unfair to students. I disagree. The point was not to evaluate their writing but rather to shed light on why so many students have trouble with the concept of a sentence—a basic concept but not a simple one.

A separate question, implicitly raised by the objectors, is whether students’ possible confusion about the questions renders the results unreliable. In response to the first tweeter, Daisy said that the questions had been field tested, that teachers had been consulted about them, and that statistical analyses had been performed on the results. Plus, she said, any inherent “tricksiness” in the questions was mitigated by the fact that that they were linked to a direct assessment of student writing.

The real issue isn’t the “tricksiness” of the multiple-choice questions. It’s the “tricksiness” built into the very concept of a sentence. The traditional approach to teaching grammar is to give students a definition: for example, that a sentence has a subject and a predicate and expresses a complete thought. But studies have found that kind of grammar instruction is too abstract for most students. They may memorize the definition, but knowing it doesn’t actually improve their writing. And the really tricksy part is “expresses a complete thought.” It’s often not obvious to students whether a group of words does that.

More recently, the prevailing assumption has been that students will just pick up concepts like what makes a sentence a sentence more or less naturally, if they read and write enough. Given Daisy’s data—and the fact that the most recent national tests in writing show that only about a quarter of eighth- and twelfth-graders scored proficient or above—that approach doesn’t seem to work for many students either.

How to help kids understand the nature of a sentence

There are two things that can work. One is to correct errors in the context of students’ own writing, ideally beginning at the sentence level—an approach that makes correcting errors a far more manageable task. When confronted with pages of error-filled prose, it’s hard to know where to begin.

The other thing that can work—and that is particularly applicable to the concept of a sentence—is “deliberate practice.” In this context, here’s what that means: A teacher gives students groups of words, some of which are sentences and some of which are fragments, and students need to identify which is which. Then they need to turn the fragments into sentences. If they engage in that activity enough, with prompt feedback, eventually they will come to understand, at more or less a gut level, what makes a sentence a sentence—at which point, if they choose to use fragments in dialogue or for poetic effect, more power to them.

This activity is one of many that form part of The Writing Revolution method. If the activity is embedded in content students are learning about, it becomes a knowledge-deepening activity: In order to turn the fragments into sentences, students need to retrieve information about the content from long-term memory and put it in their own words, boosting comprehension and retention.

Whatever you think of multiple-choice questions, it’s indisputable that far too many students struggle to make themselves understood in writing—and one reason is that they write “sentences” that aren’t really sentences. We can fix that, but it’s going to require that we recognize how difficult writing is—and that even a basic concept like the nature of a sentence is complex and therefore hard for many students to grasp. That realization should lead us to change the way we teach writing. Or maybe I should say: it should lead us to actually start teaching it.

(By the way, if you can spot the third error in the picture at the top of this post, please let me know!)

Your two priorities in fixing this problem are, as I understand them, 1) to correct students' essays and 2) to have students "deliberately" practice. Both of these are fine if your first priority is simply to first TEACH THEM WHAT CONSTITUTES A SENTENCE. Once again (as with phonics), the whole concept of simply instructing the students seems to have gone out the window in favor of somehow having them assimilate the concepts. What is this insane prejudice against simply TELLING THEM BEFOREHAND what works? When my elder daughter was in fourth grade, my wife was warning me that there was something terribly wrong with her capabilities; I thought my wife must be exaggerating. Finally, to humor her, I sat my daughter down at a table and asked her some basic questions that I thought a fourth-grader ought to know. She couldn't answer any of them. Exasperated, I finally gave her a blank sheet of paper and asked her to write a paragraph on any subject of her choice. She responded by asking what a "paragraph" is. I explained that a paragraph is a series of sentences expressing some idea. She responded by asking what a "sentence" is. Long story short, neither of our daughters ever saw the inside of a public school again. We home-schooled them. I searched in frustration for a curriculum that would teach grammar in a logical, coherent way. Finally I discovered EASY GRAMMAR, whose logical ground-up approach is unlike anything else I've ever seen. UNTIL WE START EXPLICITLY EXPLAINING THINGS TO STUDENTS in logical sequences that they can actually comprehend, we will be facing endless failure and endless hand-wringing, like this article for example. The fact that it had to be written at all, together with the fact that it does not propose EXPLICIT, DIRECT INSTRUCTION as the solution, suggests that we won't be winning this battle any time soon.

The third error is that there is no third error. But if that is the third error, then there isn't a third error. Paradox!